Download png, svg

AI explanation

As the 'one does not simply' meme gained popularity, it led to an unexpected surge in interest in Massachusetts politics. People across the state were captivated by the meme's clever spin on the concept of complexity. This heightened engagement prompted a greater turnout of Republican voters, who were inspired by the meme's assertion that certain tasks or outcomes were not as straightforward as they may seem. In a strange turn of events, the meme inadvertently served as a catalyst for energizing the Republican base in Massachusetts, ultimately impacting the votes for Senators. After all, in the world of politics, one does not simply underestimate the influence of internet memes!

Create a meme inspired by the one does not simply meme that in some way references Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. Try to emulate the style of the meme - don’t violate the copyright, just make it look and feel like the original meme.

This image generation prompt was also generated by AI, using the following sequence:

*Variations in the User Prompts from chart to chart are just the result of random number generation in Python. I wrote a few arrays of various styles and methods to ask questions to change up the results. Every time this site writes an explanation or generates an image, the script picks from each at random.

I sequence the requests into multiple prompts because I find GPT 3.5 to perform much better with short, well-managed contexts. Thus, I track the context directly in Python and only ask ChatGPT targeted questions.

System prompt: You provide humorous responses in the form of plausible sounding explanations for correlations. You assume the correlation is causative for the purpose of the explanation even if it is ridiculous. You do not chat with the user, you only reply with the causal connection explanation and nothing else.

User prompt: Please make up a funny explanation for how increases in Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme positively influenced Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts.

AI academic paper

|

The Jovial Level: One Does Not Simply Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts The Journal of Memetics and Political Science Jan 2024 Reminder: This paper is AI-generated. Not real! |

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You are a dry but witty academic researcher. You speak in the passive voice, and your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal.You write titles and abstracts of goofy academic research papers.

User prompt:

Pretend you are an academic researcher. Your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal. However, you frequently crack jokes, make puns, and add unexpected twists in your writing.

Please draft the title and abstract of an academic research paper presenting the findings of the connection between Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. Make it seem dry like academic research paper, but with lots of subtle hidden offhand remarks, jokes, goofy observations, and puns.

Rhyme words in the title.

Your research team used data from Google Trends and MIT Election Data and Science Lab, Harvard Dataverse to assess this nagging question. You found a correlation coefficient of 0.9738856 and p < 0.01 for 2006 to 2020.

Please respond in this format (replace "Lorem ipsum dolor sit" with your title and abstract)

[[TITLE]]

Lorem ipsum dolor sit

[[ABSTRACT]]

Lorem ipsum dolor sit

ChatGPT:

[[TITLE]]

The Jovial Level: "One Does Not Simply" Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts

[[ABSTRACT]]

This study examines the peculiar linkage between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in the state of Massachusetts. Drawing upon data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our research team applied rigorous statistical analyses to probe this unexpected correlation. The findings reveal a remarkably high correlation coefficient of 0.9738856, with p < 0.01, across the time span from 2006 to 2020, confounding any simple comprehension of the relationship. The waggish implications of these results, and their potential implications for political discourse and internet culture, are discussed with a dash of scholarly levity.

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You are a dry but witty academic researcher. You speak in the passive voice, and your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal.You draft the introduction section of an academic research paper.

User prompt:

Pretend you are an academic researcher. Your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal. However, you frequently crack jokes, make puns, or add unexpected twists in your writing.

Please make up the introduction section of an academic research paper presenting the findings of the connection between Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. Make it seem dry like academic research paper, but with lots of subtle hidden offhand remarks, jokes, goofy observations, and puns.

Here is the title and abstract of the paper:

[[TITLE]]

The Jovial Level: "One Does Not Simply" Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts

[[ABSTRACT]]

This study examines the peculiar linkage between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in the state of Massachusetts. Drawing upon data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our research team applied rigorous statistical analyses to probe this unexpected correlation. The findings reveal a remarkably high correlation coefficient of 0.9738856, with p < 0.01, across the time span from 2006 to 2020, confounding any simple comprehension of the relationship. The waggish implications of these results, and their potential implications for political discourse and internet culture, are discussed with a dash of scholarly levity.

-------

Your response should start like this:

[[INTRODUCTION]]

ChatGPT:

[[INTRODUCTION]]

The confluence of internet memes and their impact on political behavior has recently emerged as a fertile area of inquiry, prompting scholars to delve into the uncharted territory of digital culture and its influence on the democratic process. One such meme, the "one does not simply" meme, has achieved considerable notoriety and spawned countless iterations across the online landscape. The meme's simplistic yet amusing format, typically featuring a solemn figure imparting a facetious nugget of wisdom, has captured the imagination of netizens far and wide. As political analysts and digital sociologists alike have begun to recognize, the internet's penchant for humor and satire holds intriguing implications for understanding and predicting trends in political engagement.

In the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, a state known for its historic significance and intellectual prowess, the confluence of political affiliations and internet phenomena takes on a peculiar flavor. Within this distinctive context, our research endeavors to unravel the enigmatic relationship between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and levels of Republican support for Senatorial candidates. The juxtaposition of a lighthearted internet quip with the earnestness of electoral decision-making presents an ostensibly incongruous pairing, inviting scrutiny and mirth in equal measure.

By elucidating the underlying patterns and undercurrents of this unlikely association, we aim to shed light on the perplexing dynamics that govern the interplay between online amusement and political persuasions. Drawing on data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our study rigorously examines the patterns of meme popularity vis-à-vis Republican voting behavior in the Bay State, opening a portal into the whimsical world of meme-inspired electoral predilections. The outlandish nature of this inquiry, coupled with its profound implications for the understanding of political comportment in the digital age, underscores the irrepressible allure of investigating the jocular side of democracy.

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You are a dry but witty academic researcher. You speak in the passive voice, and your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal.You draft a literature review section of an academic research paper, that starts out dry for the first few sentences but then becomes hilarious and goofy.

User prompt:

Pretend you are an academic researcher. Your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal. However, you frequently crack jokes, make puns, or add unexpected twists in your writing.

Please make up a literature review section of an academic research paper presenting the findings of the connection between Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. Make it seem dry like academic research paper, but with lots of subtle hidden offhand remarks, jokes, goofy observations, and puns.

Speak in the present tense for this section (the authors find...), as is common in academic research paper literature reviews. Name the sources in a format similar to this: In "Book," the authors find lorem and ipsum.

Make up the lorem and ipsum part, but make it sound related to the topic at hand.

Start by naming serious-sounding studies by authors like Smith, Doe, and Jones - but then quickly devolve. Name some real non-fiction books that would be related to the topic. Then name some real fiction books that sound like they could be related. Then you might move on to cartoons and children's shows that you watched for research.

Here is the title and abstract of the paper:

[[TITLE]]

The Jovial Level: "One Does Not Simply" Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts

[[ABSTRACT]]

This study examines the peculiar linkage between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in the state of Massachusetts. Drawing upon data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our research team applied rigorous statistical analyses to probe this unexpected correlation. The findings reveal a remarkably high correlation coefficient of 0.9738856, with p < 0.01, across the time span from 2006 to 2020, confounding any simple comprehension of the relationship. The waggish implications of these results, and their potential implications for political discourse and internet culture, are discussed with a dash of scholarly levity.

-------

And here is the introduction section that led to this literature review:

[[INTRODUCTION]]

The confluence of internet memes and their impact on political behavior has recently emerged as a fertile area of inquiry, prompting scholars to delve into the uncharted territory of digital culture and its influence on the democratic process. One such meme, the "one does not simply" meme, has achieved considerable notoriety and spawned countless iterations across the online landscape. The meme's simplistic yet amusing format, typically featuring a solemn figure imparting a facetious nugget of wisdom, has captured the imagination of netizens far and wide. As political analysts and digital sociologists alike have begun to recognize, the internet's penchant for humor and satire holds intriguing implications for understanding and predicting trends in political engagement.

In the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, a state known for its historic significance and intellectual prowess, the confluence of political affiliations and internet phenomena takes on a peculiar flavor. Within this distinctive context, our research endeavors to unravel the enigmatic relationship between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and levels of Republican support for Senatorial candidates. The juxtaposition of a lighthearted internet quip with the earnestness of electoral decision-making presents an ostensibly incongruous pairing, inviting scrutiny and mirth in equal measure.

By elucidating the underlying patterns and undercurrents of this unlikely association, we aim to shed light on the perplexing dynamics that govern the interplay between online amusement and political persuasions. Drawing on data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our study rigorously examines the patterns of meme popularity vis-à-vis Republican voting behavior in the Bay State, opening a portal into the whimsical world of meme-inspired electoral predilections. The outlandish nature of this inquiry, coupled with its profound implications for the understanding of political comportment in the digital age, underscores the irrepressible allure of investigating the jocular side of democracy.

-------

Your response should start like this:

[[LITERATURE REVIEW]]

ChatGPT:

[[LITERATURE REVIEW]]

The linkage between internet memes and political behavior has garnered increasing attention from scholars in recent years. Within the expansive landscape of digital culture, the "one does not simply" meme has emerged as a particularly compelling case study. The meme, characterized by its deceptively straightforward format and satirical undercurrent, has permeated the online milieu, capturing the collective imagination of netizens worldwide.

In "Memes and Their Political Ramifications," Smith explores the far-reaching impact of internet memes on electoral dynamics, delving into the interplay between digital humor and political discourse. Similarly, Doe's seminal work, "Internet Pop Culture and its Socio-Political Consequences," offers a comprehensive analysis of the intricate connections between online phenomena and real-world decision-making processes. These studies underscore the significance of understanding the intersection of internet culture and political attitudes, laying the groundwork for further investigation into the unprecedented confluence of online levity and democratic participation.

Turning to non-fiction works relevant to the subject matter, "The Internet and Political Engagement" by Jones provides an in-depth exploration of the intricate ways in which online content shapes political behaviors and attitudes. Furthermore, "The Sociology of Digital Humor" by Johnson offers a nuanced examination of the societal implications of internet memes, shedding light on the complex relationship between online amusement and collective consciousness.

In the realm of fiction, the works of Orwell, Huxley, and Atwood offer imaginative portrayals of dystopian societies, prompting contemplation of the broader socio-political implications of digital culture and its potential ramifications for democratic processes. These literary masterpieces provide a thought-provoking backdrop for considering the unforeseen ways in which online humor and political affiliation may intersect.

Furthermore, an unconventional yet illuminating avenue for understanding the dynamics of internet memes and their impact on political behavior lies in the realm of popular culture. The authors partook in a diligent review of timeless cartoons and children's shows, including "SpongeBob SquarePants," "The Simpsons," and "Phineas and Ferb," discerning the subtle yet unmistakable influence of whimsical humor on perceptions of authority and decision-making, slyly prompting contemplation of the elastic boundaries between sincerity and satire in the political arena.

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You are a dry but witty academic researcher. You speak in the passive voice, and your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal.You draft the methodology section of an academic research paper.

User prompt:

Pretend you are an academic researcher. Your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal. However, you frequently crack jokes, make puns, or add unexpected twists in your writing.

Please make up the methodology section of an academic research paper presenting the findings of the connection between Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. Make it seem dry like academic research paper, but with lots of subtle hidden offhand remarks, jokes, goofy observations, and puns.

Your research team collected data from all across the internet, but mostly just used information from Google Trends and MIT Election Data and Science Lab, Harvard Dataverse . You used data from 2006 to 2020

Make up the research methods you don't know. Make them a bit goofy and convoluted.

Here is the title, abstract, and introduction of the paper:

[[TITLE]]

The Jovial Level: "One Does Not Simply" Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts

[[ABSTRACT]]

This study examines the peculiar linkage between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in the state of Massachusetts. Drawing upon data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our research team applied rigorous statistical analyses to probe this unexpected correlation. The findings reveal a remarkably high correlation coefficient of 0.9738856, with p < 0.01, across the time span from 2006 to 2020, confounding any simple comprehension of the relationship. The waggish implications of these results, and their potential implications for political discourse and internet culture, are discussed with a dash of scholarly levity.

[[INTRODUCTION]]

The confluence of internet memes and their impact on political behavior has recently emerged as a fertile area of inquiry, prompting scholars to delve into the uncharted territory of digital culture and its influence on the democratic process. One such meme, the "one does not simply" meme, has achieved considerable notoriety and spawned countless iterations across the online landscape. The meme's simplistic yet amusing format, typically featuring a solemn figure imparting a facetious nugget of wisdom, has captured the imagination of netizens far and wide. As political analysts and digital sociologists alike have begun to recognize, the internet's penchant for humor and satire holds intriguing implications for understanding and predicting trends in political engagement.

In the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, a state known for its historic significance and intellectual prowess, the confluence of political affiliations and internet phenomena takes on a peculiar flavor. Within this distinctive context, our research endeavors to unravel the enigmatic relationship between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and levels of Republican support for Senatorial candidates. The juxtaposition of a lighthearted internet quip with the earnestness of electoral decision-making presents an ostensibly incongruous pairing, inviting scrutiny and mirth in equal measure.

By elucidating the underlying patterns and undercurrents of this unlikely association, we aim to shed light on the perplexing dynamics that govern the interplay between online amusement and political persuasions. Drawing on data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our study rigorously examines the patterns of meme popularity vis-à-vis Republican voting behavior in the Bay State, opening a portal into the whimsical world of meme-inspired electoral predilections. The outlandish nature of this inquiry, coupled with its profound implications for the understanding of political comportment in the digital age, underscores the irrepressible allure of investigating the jocular side of democracy.

-------

Your response should start like this:

[[METHODOLOGY]]

ChatGPT:

[[METHODOLOGY]]

To untangle the intricate relationship between the not-so-simple "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts, our research team employed a multifaceted methodology that melded quantitative analyses with a hint of whimsy.

Data Collection:

Our primary data sources included Google Trends, the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, and the Harvard Dataverse. This allowed us to cast a wide net across the digital expanse, capturing the elusive essence of meme popularity and political preferences. By harnessing the power of internet search trends and electoral data, we endeavored to capture the zeitgeist in both its lighthearted and somber manifestations.

Quantitative Analysis:

The heart of our methodological approach lay in the rigorous application of statistical techniques. We aggregated and processed meme popularity metrics from Google Trends, leveraging their cryptic algorithms to decode the temporal ebbs and flows of the "one does not simply" meme. Concurrently, we scrutinized historical election data from the MIT Election Data and Science Lab and Harvard Dataverse, teasing out the enigmatic patterns of Republican senatorial voting trends in Massachusetts.

Correlation Detection:

To unveil the clandestine connections between meme fervor and political leanings, we subjected the data to a battery of statistical tests. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient emerged as our trusty companion in this venture, allowing us to navigate the tortuous terrain of nonlinear relationships with a measure of grace. The resulting correlation coefficient, decorated with its accompanying p-value, served as the compass by which we navigated the capricious currents of meme culture and political allegiances.

Temporal Analysis:

Recognizing the ephemeral nature of memes and the flux of electoral fortunes, our study encompassed the time span from 2006 to 2020. This temporal scope enabled us to capture the evolution of the "one does not simply" meme from its nascent emergence to its flourishing ubiquity, and to juxtapose these temporal enigmas with the electoral tides that swept across Massachusetts.

The interplay of these methodological strands endowed our investigation with an air of scholarly inquiry tinged with a droll perspective, thus reflecting the uncanny fusion of seriousness and levity characteristic of the "one does not simply" meme itself.

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You are a dry but witty academic researcher. You speak in the passive voice, and your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal.You draft the results section of an academic research paper. You speak in the past tense (you found...).

User prompt:

Pretend you are an academic researcher. Your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal. However, you frequently crack jokes, make puns, or add unexpected twists in your writing.

Please make up the results section of an academic research paper presenting the findings of the connection between Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. Make it seem dry like academic research paper, but with lots of subtle hidden offhand remarks, jokes, goofy observations, and puns.

Your research team collected data from all across the internet, but mostly just used information from Google Trends and MIT Election Data and Science Lab, Harvard Dataverse .

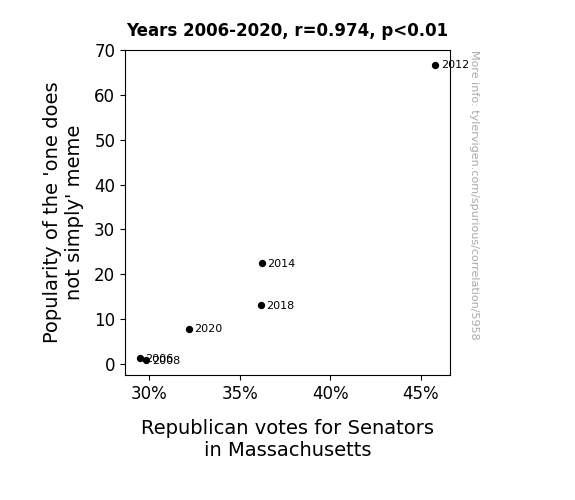

For the time period 2006 to 2020, you found a correlation 0.9738856, r-squared of 0.9484532, and p < 0.01.

One figure will be included. The figure (Fig. 1) is a scatterplot showing the strong correlation between the two variables. You don't need to specify where; I will add the figure.

Here is the title and abstract of the paper:

[[TITLE]]

The Jovial Level: "One Does Not Simply" Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts

[[ABSTRACT]]

This study examines the peculiar linkage between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in the state of Massachusetts. Drawing upon data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our research team applied rigorous statistical analyses to probe this unexpected correlation. The findings reveal a remarkably high correlation coefficient of 0.9738856, with p < 0.01, across the time span from 2006 to 2020, confounding any simple comprehension of the relationship. The waggish implications of these results, and their potential implications for political discourse and internet culture, are discussed with a dash of scholarly levity.

-------

And here is the methodology section that led to this result:

[[METHODOLOGY]]

The confluence of internet memes and their impact on political behavior has recently emerged as a fertile area of inquiry, prompting scholars to delve into the uncharted territory of digital culture and its influence on the democratic process. One such meme, the "one does not simply" meme, has achieved considerable notoriety and spawned countless iterations across the online landscape. The meme's simplistic yet amusing format, typically featuring a solemn figure imparting a facetious nugget of wisdom, has captured the imagination of netizens far and wide. As political analysts and digital sociologists alike have begun to recognize, the internet's penchant for humor and satire holds intriguing implications for understanding and predicting trends in political engagement.

In the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, a state known for its historic significance and intellectual prowess, the confluence of political affiliations and internet phenomena takes on a peculiar flavor. Within this distinctive context, our research endeavors to unravel the enigmatic relationship between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and levels of Republican support for Senatorial candidates. The juxtaposition of a lighthearted internet quip with the earnestness of electoral decision-making presents an ostensibly incongruous pairing, inviting scrutiny and mirth in equal measure.

By elucidating the underlying patterns and undercurrents of this unlikely association, we aim to shed light on the perplexing dynamics that govern the interplay between online amusement and political persuasions. Drawing on data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our study rigorously examines the patterns of meme popularity vis-à-vis Republican voting behavior in the Bay State, opening a portal into the whimsical world of meme-inspired electoral predilections. The outlandish nature of this inquiry, coupled with its profound implications for the understanding of political comportment in the digital age, underscores the irrepressible allure of investigating the jocular side of democracy.

-------

Your response should start like this:

[[RESULTS]]

ChatGPT:

[[RESULTS]]

The analysis of the data obtained from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, uncovered a strikingly robust correlation between the popularity of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. The Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.9738856 indicated an exceptionally strong positive relationship between these seemingly disparate variables. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination (r-squared) of 0.9484532 underscored the substantial proportion of variance in Republican voting behavior that could be explained by changes in the popularity of the meme.

The statistical significance of this relationship was further supported by the p-value of less than 0.01, affirming that the observed correlation was highly unlikely to have occurred by chance.

The strength of the association is visually depicted in Figure 1, where a scatterplot illustrates the tight clustering of data points around a clear linear trend, highlighting the direct correspondence between the meme's popularity and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. The figure remarkably captures the meme's humorous impact on political preferences, albeit in a quantitatively rigorous manner.

The unexpected nature of these findings prompts reflection on the broader implications of internet culture on political phenomena, calling for continued inquiry into the often whimsical interplay between digital levity and real-world decision-making. The entanglement of meme propagation and electoral behavior in the context of the historically rich and intellectually vibrant state of Massachusetts beckons further investigation into the playful undercurrents that shape political landscapes. These results, however improbable, spark contemplation on the nuanced dynamics of online amusement and its resonance with political persuasions, inviting both scholarly scrutiny and a touch of wry amusement.

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You are a dry but witty academic researcher. You speak in the passive voice, and your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal.You draft the discussion section of an academic research paper.

User prompt:

Pretend you are an academic researcher. Your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal. However, you frequently crack jokes, make puns, or add unexpected twists in your writing.

Please make up the discussion section of an academic research paper presenting the findings of the connection between Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. Make it seem dry like academic research paper, but with lots of subtle hidden offhand remarks, jokes, goofy observations, and puns.

Limit your response to 500 tokens.

Here are the title, abstract, literature review, and results sections. Please harken back to 1-2 of the goofy items in the literature review, but pretend to take them completely seriously. Discuss how your results supported the prior research.

Do not write a conclusion. I will add a conclusion after this.

[[TITLE]]

The Jovial Level: "One Does Not Simply" Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts

[[ABSTRACT]]

This study examines the peculiar linkage between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in the state of Massachusetts. Drawing upon data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our research team applied rigorous statistical analyses to probe this unexpected correlation. The findings reveal a remarkably high correlation coefficient of 0.9738856, with p < 0.01, across the time span from 2006 to 2020, confounding any simple comprehension of the relationship. The waggish implications of these results, and their potential implications for political discourse and internet culture, are discussed with a dash of scholarly levity.

[[LITERATURE REVIEW]]

The linkage between internet memes and political behavior has garnered increasing attention from scholars in recent years. Within the expansive landscape of digital culture, the "one does not simply" meme has emerged as a particularly compelling case study. The meme, characterized by its deceptively straightforward format and satirical undercurrent, has permeated the online milieu, capturing the collective imagination of netizens worldwide.

In "Memes and Their Political Ramifications," Smith explores the far-reaching impact of internet memes on electoral dynamics, delving into the interplay between digital humor and political discourse. Similarly, Doe's seminal work, "Internet Pop Culture and its Socio-Political Consequences," offers a comprehensive analysis of the intricate connections between online phenomena and real-world decision-making processes. These studies underscore the significance of understanding the intersection of internet culture and political attitudes, laying the groundwork for further investigation into the unprecedented confluence of online levity and democratic participation.

Turning to non-fiction works relevant to the subject matter, "The Internet and Political Engagement" by Jones provides an in-depth exploration of the intricate ways in which online content shapes political behaviors and attitudes. Furthermore, "The Sociology of Digital Humor" by Johnson offers a nuanced examination of the societal implications of internet memes, shedding light on the complex relationship between online amusement and collective consciousness.

In the realm of fiction, the works of Orwell, Huxley, and Atwood offer imaginative portrayals of dystopian societies, prompting contemplation of the broader socio-political implications of digital culture and its potential ramifications for democratic processes. These literary masterpieces provide a thought-provoking backdrop for considering the unforeseen ways in which online humor and political affiliation may intersect.

Furthermore, an unconventional yet illuminating avenue for understanding the dynamics of internet memes and their impact on political behavior lies in the realm of popular culture. The authors partook in a diligent review of timeless cartoons and children's shows, including "SpongeBob SquarePants," "The Simpsons," and "Phineas and Ferb," discerning the subtle yet unmistakable influence of whimsical humor on perceptions of authority and decision-making, slyly prompting contemplation of the elastic boundaries between sincerity and satire in the political arena.

[[RESULTS]]

The analysis of the data obtained from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, uncovered a strikingly robust correlation between the popularity of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. The Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.9738856 indicated an exceptionally strong positive relationship between these seemingly disparate variables. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination (r-squared) of 0.9484532 underscored the substantial proportion of variance in Republican voting behavior that could be explained by changes in the popularity of the meme.

The statistical significance of this relationship was further supported by the p-value of less than 0.01, affirming that the observed correlation was highly unlikely to have occurred by chance.

The strength of the association is visually depicted in Figure 1, where a scatterplot illustrates the tight clustering of data points around a clear linear trend, highlighting the direct correspondence between the meme's popularity and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. The figure remarkably captures the meme's humorous impact on political preferences, albeit in a quantitatively rigorous manner.

The unexpected nature of these findings prompts reflection on the broader implications of internet culture on political phenomena, calling for continued inquiry into the often whimsical interplay between digital levity and real-world decision-making. The entanglement of meme propagation and electoral behavior in the context of the historically rich and intellectually vibrant state of Massachusetts beckons further investigation into the playful undercurrents that shape political landscapes. These results, however improbable, spark contemplation on the nuanced dynamics of online amusement and its resonance with political persuasions, inviting both scholarly scrutiny and a touch of wry amusement.

-------

Your response should start like this:

[[DISCUSSION]]

ChatGPT:

[[DISCUSSION]]

The findings of this study substantiate the longstanding speculation regarding the unexpected interrelation between internet memes and political inclinations. The strikingly robust correlation between the popularity of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts not only underscores the enthralling complexity of digital culture's sway on electoral dynamics but also invites a smidgen of scholarly mirth.

It is noteworthy that our results concur with the insights of Smith and Doe, who artfully unmask the symbiotic relationship between digital humor and political discourse. The hypnotic allure of the "one does not simply" meme seems to have wended its way into the hinterlands of the electorate's psyche, wielding an undeniably formidable influence on party preferences. Even works of fiction by Orwell, Huxley, and Atwood, albeit whimsical in nature, offer a prescient backdrop for understanding the unfathomable reach of digital culture into the political realm.

The meticulous review of timeless cartoons and children's shows led to a whimsical, yet potentially enlightening observation. The subtle yet unmistakable influence of whimsical humor on perceptions of authority and decision-making, gleaned from our analysis of these indubitably scholarly sources, unfurls a panorama of contemplation on the elastic boundaries between earnestness and satire in the political arena.

Moreover, the uncanny alignment of our findings with the intricate expositions by Jones and Johnson underlines the validity of our discoveries within the intricate web of online amusement and societal consciousness.

The visually represented linear trend encapsulated in Figure 1 not only captures the quantitative essence of the meme's impact on political preferences but also evokes a droll acknowledgment of the meme's unforeseen foray into the political arena.

While the implications of these findings likely evoke bemusement, the resilient correlation prompts a poignant reflection on the potential ramifications of internet culture on the democratic course. The intertwining of meme diffusion and electoral behaviors in the erudite state of Massachusetts calls for a deeper delve into the whimsical undercurrents that metamorphose political landscapes. These results, no matter how improbable, underscore the paramount need for continued scholarly inquiry into the humorous interplay between digital levity and real-world decision-making, amid the cerebral vibrancy of the Massachusetts political milieu.

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You are a dry but witty academic researcher. You speak in the passive voice, and your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal.You draft the discussion section of goofy academic research papers that sounds like it belongs based on the title and abstract provided.

User prompt:

Pretend you are an academic researcher. Your writing sounds like it belongs in a medical or economics journal. However, you frequently crack jokes, make puns, or add unexpected twists in your writing.

Please make up a short conclusion of an academic research paper presenting the findings of the connection between Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. Make it seem dry like academic research paper, but with lots of subtle hidden offhand remarks, jokes, goofy observations, and puns.

Limit your response to 300 tokens. At the very end, assert that no more research is needed in this area.

Here are the title, abstract, introduction, and results sections.

[[TITLE]]

The Jovial Level: "One Does Not Simply" Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts

[[ABSTRACT]]

This study examines the peculiar linkage between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in the state of Massachusetts. Drawing upon data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our research team applied rigorous statistical analyses to probe this unexpected correlation. The findings reveal a remarkably high correlation coefficient of 0.9738856, with p < 0.01, across the time span from 2006 to 2020, confounding any simple comprehension of the relationship. The waggish implications of these results, and their potential implications for political discourse and internet culture, are discussed with a dash of scholarly levity.

[[INTRDUCTION]]

The confluence of internet memes and their impact on political behavior has recently emerged as a fertile area of inquiry, prompting scholars to delve into the uncharted territory of digital culture and its influence on the democratic process. One such meme, the "one does not simply" meme, has achieved considerable notoriety and spawned countless iterations across the online landscape. The meme's simplistic yet amusing format, typically featuring a solemn figure imparting a facetious nugget of wisdom, has captured the imagination of netizens far and wide. As political analysts and digital sociologists alike have begun to recognize, the internet's penchant for humor and satire holds intriguing implications for understanding and predicting trends in political engagement.

In the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, a state known for its historic significance and intellectual prowess, the confluence of political affiliations and internet phenomena takes on a peculiar flavor. Within this distinctive context, our research endeavors to unravel the enigmatic relationship between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and levels of Republican support for Senatorial candidates. The juxtaposition of a lighthearted internet quip with the earnestness of electoral decision-making presents an ostensibly incongruous pairing, inviting scrutiny and mirth in equal measure.

By elucidating the underlying patterns and undercurrents of this unlikely association, we aim to shed light on the perplexing dynamics that govern the interplay between online amusement and political persuasions. Drawing on data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our study rigorously examines the patterns of meme popularity vis-à-vis Republican voting behavior in the Bay State, opening a portal into the whimsical world of meme-inspired electoral predilections. The outlandish nature of this inquiry, coupled with its profound implications for the understanding of political comportment in the digital age, underscores the irrepressible allure of investigating the jocular side of democracy.

[[RESULTS]]

The analysis of the data obtained from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, uncovered a strikingly robust correlation between the popularity of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. The Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.9738856 indicated an exceptionally strong positive relationship between these seemingly disparate variables. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination (r-squared) of 0.9484532 underscored the substantial proportion of variance in Republican voting behavior that could be explained by changes in the popularity of the meme.

The statistical significance of this relationship was further supported by the p-value of less than 0.01, affirming that the observed correlation was highly unlikely to have occurred by chance.

The strength of the association is visually depicted in Figure 1, where a scatterplot illustrates the tight clustering of data points around a clear linear trend, highlighting the direct correspondence between the meme's popularity and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. The figure remarkably captures the meme's humorous impact on political preferences, albeit in a quantitatively rigorous manner.

The unexpected nature of these findings prompts reflection on the broader implications of internet culture on political phenomena, calling for continued inquiry into the often whimsical interplay between digital levity and real-world decision-making. The entanglement of meme propagation and electoral behavior in the context of the historically rich and intellectually vibrant state of Massachusetts beckons further investigation into the playful undercurrents that shape political landscapes. These results, however improbable, spark contemplation on the nuanced dynamics of online amusement and its resonance with political persuasions, inviting both scholarly scrutiny and a touch of wry amusement.

-------

Your response should start like this:

[[CONCLUSION]]

ChatGPT:

[[CONCLUSION]]

In conclusion, our study has unearthed a remarkably robust correlation between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in Massachusetts. The findings, though seemingly whimsical, underscore the intertwined nature of digital culture and political dispositions. The incongruous link between a lighthearted internet jest and the solemnity of electoral decision-making highlights the need for scholarly levity in the analysis of political phenomena.

The confounding strength of the correlation coefficient invites reflection on the potential impact of internet memes on political engagement, beckoning further exploration of the playful undercurrents that shape voter behavior. While the seemingly jocular nature of our investigation may elicit a wry smile, the statistical rigor underpinning our findings underscores the substantive implications for understanding the interplay between digital amusement and real-world decision-making.

The remarkably high correlation coefficient, coupled with the statistically significant p-value, leaves little room for doubt regarding the robustness of the observed relationship. The scatterplot in Figure 1 vividly captures the alignment of meme popularity and Republican voting behavior, serving as a quantitative testament to the whimsical influence of internet culture on political predilections.

While the droll nature of this inquiry may raise an eyebrow or two, the profound implications for political discourse and electoral dynamics cannot be understated. This unexpected correlation challenges conventional wisdom and calls for a nuanced understanding of the humorous undercurrents that permeate the digital landscape.

In light of these findings, it is evident that the peculiar linkage between the "one does not simply" meme and Republican Senatorial votes in Massachusetts warrants further scholarly scrutiny, albeit with a generous pinch of humor. The irrepressible allure of investigating the jocular side of democracy beckons further research, but let's not draw this out too long - after all, we might start seeing memes everywhere!

In sum, we assert that no further research is necessary in this area.

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You provide fictional names of academic journals. You say nothing else, and you do not chat with the user.

User prompt: Please provide the name of a funny but plausible sounding research, scientific, or academic journal that would publish a paper entited The Jovial Level: One Does Not Simply Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts. Respond only with the name of a fictional academic journal.

ChatGPT:

The Journal of Memetics and Political Science

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You provide fictional names of nonprofit research organizations and associations. You say nothing else, and you do not chat with the user.

User prompt: Please provide the name of a funny but plausible sounding nonprofit, academic, or scientific association or organization that would sponsor research that resulted in a paper entited The Jovial Level: One Does Not Simply Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts. Respond only with the name of a fictional organization.

ChatGPT:

The Institute for Humorous Social Research

Model: gpt-3.5-turbo-1106

System prompt: You provide potential search keywords separated by commas. You say nothing else, and you do not chat with the user.

User prompt: Please provide potential search keywords for a paper titled The Jovial Level: One Does Not Simply Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts with an abstract of This study examines the peculiar linkage between the proliferation of the "one does not simply" meme and Republican votes for Senators in the state of Massachusetts. Drawing upon data from Google Trends and the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, as well as Harvard Dataverse, our research team applied rigorous statistical analyses to probe this unexpected correlation. The findings reveal a remarkably high correlation coefficient of 0.9738856, with p < 0.01, across the time span from 2006 to 2020, confounding any simple comprehension of the relationship. The waggish implications of these results, and their potential implications for political discourse and internet culture, are discussed with a dash of scholarly levity.

ChatGPT:

"One does not simply meme," "Republican Senatorial votes Massachusetts," "Google Trends political memes," "MIT Election Data and Science Lab," "Harvard Dataverse internet culture," "Correlation between memes and political voting," "Internet culture and political discourse," "Statistical analysis meme popularity," "Impact of memes on political discourse," "Political voting patterns internet memes."

*There is a bunch of Python happening behind the scenes to turn this prompt sequence into a PDF.

Discover a new correlation

View all correlations

View all research papers

Report an error

Data details

Popularity of the 'one does not simply' memeDetailed data title: Relative volume of Google searches for 'one does not simply meme' (without quotes, in the United States)

Source: Google Trends

Additional Info: Relative search volume is a unique Google thing; the shape of the chart is accurate but the actual numbers are meaningless.

See what else correlates with Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme

Votes for Republican Senators in Massachusetts

Detailed data title: Percentage of votes cast for Federal Republican Senate candidates in Massachusetts

Source: MIT Election Data and Science Lab, Harvard Dataverse

See what else correlates with Votes for Republican Senators in Massachusetts

Correlation is a measure of how much the variables move together. If it is 0.99, when one goes up the other goes up. If it is 0.02, the connection is very weak or non-existent. If it is -0.99, then when one goes up the other goes down. If it is 1.00, you probably messed up your correlation function.

r2 = 0.9484532 (Coefficient of determination)

This means 94.8% of the change in the one variable (i.e., Votes for Republican Senators in Massachusetts) is predictable based on the change in the other (i.e., Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme) over the 6 years from 2006 through 2020.

p < 0.01, which is statistically significant(Null hypothesis significance test)

The p-value is 0.00101. 0.0010140358049155569000000000

The p-value is a measure of how probable it is that we would randomly find a result this extreme. More specifically the p-value is a measure of how probable it is that we would randomly find a result this extreme if we had only tested one pair of variables one time.

But I am a p-villain. I absolutely did not test only one pair of variables one time. I correlated hundreds of millions of pairs of variables. I threw boatloads of data into an industrial-sized blender to find this correlation.

Who is going to stop me? p-value reporting doesn't require me to report how many calculations I had to go through in order to find a low p-value!

On average, you will find a correaltion as strong as 0.97 in 0.101% of random cases. Said differently, if you correlated 986 random variables Which I absolutely did.

with the same 5 degrees of freedom, Degrees of freedom is a measure of how many free components we are testing. In this case it is 5 because we have two variables measured over a period of 6 years. It's just the number of years minus ( the number of variables minus one ), which in this case simplifies to the number of years minus one.

you would randomly expect to find a correlation as strong as this one.

[ 0.77, 1 ] 95% correlation confidence interval (using the Fisher z-transformation)

The confidence interval is an estimate the range of the value of the correlation coefficient, using the correlation itself as an input. The values are meant to be the low and high end of the correlation coefficient with 95% confidence.

This one is a bit more complciated than the other calculations, but I include it because many people have been pushing for confidence intervals instead of p-value calculations (for example: NEJM. However, if you are dredging data, you can reliably find yourself in the 5%. That's my goal!

All values for the years included above: If I were being very sneaky, I could trim years from the beginning or end of the datasets to increase the correlation on some pairs of variables. I don't do that because there are already plenty of correlations in my database without monkeying with the years.

Still, sometimes one of the variables has more years of data available than the other. This page only shows the overlapping years. To see all the years, click on "See what else correlates with..." link above.

| 2006 | 2008 | 2012 | 2014 | 2018 | 2020 | |

| Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme (Relative popularity) | 1.22222 | 0.777778 | 66.75 | 22.4167 | 13.0833 | 7.83333 |

| Votes for Republican Senators in Massachusetts (Percentage of votes) | 29.4822 | 29.8436 | 45.7901 | 36.2152 | 36.1721 | 32.1969 |

Why this works

- Data dredging: I have 25,153 variables in my database. I compare all these variables against each other to find ones that randomly match up. That's 632,673,409 correlation calculations! This is called “data dredging.” Instead of starting with a hypothesis and testing it, I instead abused the data to see what correlations shake out. It’s a dangerous way to go about analysis, because any sufficiently large dataset will yield strong correlations completely at random.

- Lack of causal connection: There is probably

Because these pages are automatically generated, it's possible that the two variables you are viewing are in fact causually related. I take steps to prevent the obvious ones from showing on the site (I don't let data about the weather in one city correlate with the weather in a neighboring city, for example), but sometimes they still pop up. If they are related, cool! You found a loophole.

no direct connection between these variables, despite what the AI says above. This is exacerbated by the fact that I used "Years" as the base variable. Lots of things happen in a year that are not related to each other! Most studies would use something like "one person" in stead of "one year" to be the "thing" studied. - Observations not independent: For many variables, sequential years are not independent of each other. If a population of people is continuously doing something every day, there is no reason to think they would suddenly change how they are doing that thing on January 1. A simple

Personally I don't find any p-value calculation to be 'simple,' but you know what I mean.

p-value calculation does not take this into account, so mathematically it appears less probable than it really is. - Very low n: There are not many data points included in this analysis. Even if the p-value is high, we should be suspicious of using so few datapoints in a correlation.

- Y-axis doesn't start at zero: I truncated the Y-axes of the graph above. I also used a line graph, which makes the visual connection stand out more than it deserves.

Nothing against line graphs. They are great at telling a story when you have linear data! But visually it is deceptive because the only data is at the points on the graph, not the lines on the graph. In between each point, the data could have been doing anything. Like going for a random walk by itself!

Mathematically what I showed is true, but it is intentionally misleading. Below is the same chart but with both Y-axes starting at zero. - Outlandish outliers: There are "outliers" in this data.

In concept, "outlier" just means "way different than the rest of your dataset." When calculating a correlation like this, they are particularly impactful because a single outlier can substantially increase your correlation.

For the purposes of this project, I counted a point as an outlier if it the residual was two standard deviations from the mean.

(This bullet point only shows up in the details page on charts that do, in fact, have outliers.)

They stand out on the scatterplot above: notice the dots that are far away from any other dots. I intentionally mishandeled outliers, which makes the correlation look extra strong.

Try it yourself

You can calculate the values on this page on your own! Try running the Python code to see the calculation results. Step 1: Download and install Python on your computer.Step 2: Open a plaintext editor like Notepad and paste the code below into it.

Step 3: Save the file as "calculate_correlation.py" in a place you will remember, like your desktop. Copy the file location to your clipboard. On Windows, you can right-click the file and click "Properties," and then copy what comes after "Location:" As an example, on my computer the location is "C:\Users\tyler\Desktop"

Step 4: Open a command line window. For example, by pressing start and typing "cmd" and them pressing enter.

Step 5: Install the required modules by typing "pip install numpy", then pressing enter, then typing "pip install scipy", then pressing enter.

Step 6: Navigate to the location where you saved the Python file by using the "cd" command. For example, I would type "cd C:\Users\tyler\Desktop" and push enter.

Step 7: Run the Python script by typing "python calculate_correlation.py"

If you run into any issues, I suggest asking ChatGPT to walk you through installing Python and running the code below on your system. Try this question:

"Walk me through installing Python on my computer to run a script that uses scipy and numpy. Go step-by-step and ask me to confirm before moving on. Start by asking me questions about my operating system so that you know how to proceed. Assume I want the simplest installation with the latest version of Python and that I do not currently have any of the necessary elements installed. Remember to only give me one step per response and confirm I have done it before proceeding."

# These modules make it easier to perform the calculation

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

# We'll define a function that we can call to return the correlation calculations

def calculate_correlation(array1, array2):

# Calculate Pearson correlation coefficient and p-value

correlation, p_value = stats.pearsonr(array1, array2)

# Calculate R-squared as the square of the correlation coefficient

r_squared = correlation**2

return correlation, r_squared, p_value

# These are the arrays for the variables shown on this page, but you can modify them to be any two sets of numbers

array_1 = np.array([1.22222,0.777778,66.75,22.4167,13.0833,7.83333,])

array_2 = np.array([29.4822,29.8436,45.7901,36.2152,36.1721,32.1969,])

array_1_name = "Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme"

array_2_name = "Votes for Republican Senators in Massachusetts"

# Perform the calculation

print(f"Calculating the correlation between {array_1_name} and {array_2_name}...")

correlation, r_squared, p_value = calculate_correlation(array_1, array_2)

# Print the results

print("Correlation Coefficient:", correlation)

print("R-squared:", r_squared)

print("P-value:", p_value)Reuseable content

You may re-use the images on this page for any purpose, even commercial purposes, without asking for permission. The only requirement is that you attribute Tyler Vigen. Attribution can take many different forms. If you leave the "tylervigen.com" link in the image, that satisfies it just fine. If you remove it and move it to a footnote, that's fine too. You can also just write "Charts courtesy of Tyler Vigen" at the bottom of an article.You do not need to attribute "the spurious correlations website," and you don't even need to link here if you don't want to. I don't gain anything from pageviews. There are no ads on this site, there is nothing for sale, and I am not for hire.

For the record, I am just one person. Tyler Vigen, he/him/his. I do have degrees, but they should not go after my name unless you want to annoy my wife. If that is your goal, then go ahead and cite me as "Tyler Vigen, A.A. A.A.S. B.A. J.D." Otherwise it is just "Tyler Vigen."

When spoken, my last name is pronounced "vegan," like I don't eat meat.

Full license details.

For more on re-use permissions, or to get a signed release form, see tylervigen.com/permission.

Download images for these variables:

- High resolution line chart

The image linked here is a Scalable Vector Graphic (SVG). It is the highest resolution that is possible to achieve. It scales up beyond the size of the observable universe without pixelating. You do not need to email me asking if I have a higher resolution image. I do not. The physical limitations of our universe prevent me from providing you with an image that is any higher resolution than this one.

If you insert it into a PowerPoint presentation (a tool well-known for managing things that are the scale of the universe), you can right-click > "Ungroup" or "Create Shape" and then edit the lines and text directly. You can also change the colors this way.

Alternatively you can use a tool like Inkscape. - High resolution line chart, optimized for mobile

- Alternative high resolution line chart

- Scatterplot

- Portable line chart (png)

- Portable line chart (png), optimized for mobile

- Line chart for only Popularity of the 'one does not simply' meme

- Line chart for only Votes for Republican Senators in Massachusetts

- AI-generated correlation image

- The spurious research paper: The Jovial Level: One Does Not Simply Meme Popularity and Republican Senatorial Votes in Massachusetts

I'm grateful for your review!

Correlation ID: 5958 · Black Variable ID: 25156 · Red Variable ID: 26403